Greetings! I want to tell you about some changes to the add-ons manager you’ll be seeing in Firefox’s trunk release very soon.

Add-ons in the Content Area, Oh my!

The biggest change you’ll see is that the add-ons manager will no longer appear in a separate window, but in a tab in Firefox’s content space. This represents a big shift in Firefox’s interaction model. You can read more about the reasons for in-content display here, but the summary is that displaying in content:

- Allows for similar display across devices

- Allows for quick updates from external sites, like Mozilla Add-ons (AMO)

- Gives more screen real estate to tasks, allowing for less constrained interaction

- Eliminates the need to manage small, easily-hidden windows

Eventually, we’d like to move many of Firefox’s various “extra” windows (Download Manager, Bookmarks Library, etc) into the content area. The add-ons manager, by being the first, will hopefully provide a solid working model that will guide the redesign and improvement of Firefox’s other windows.

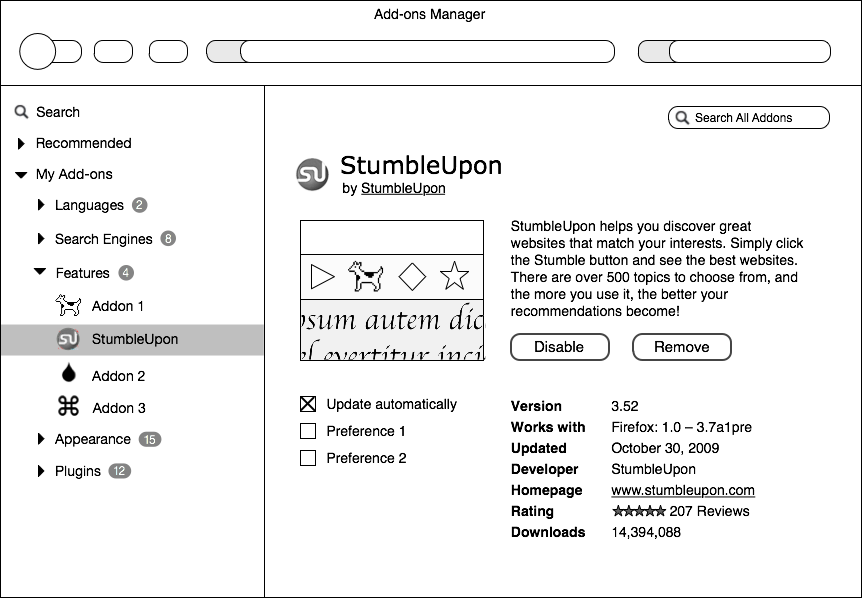

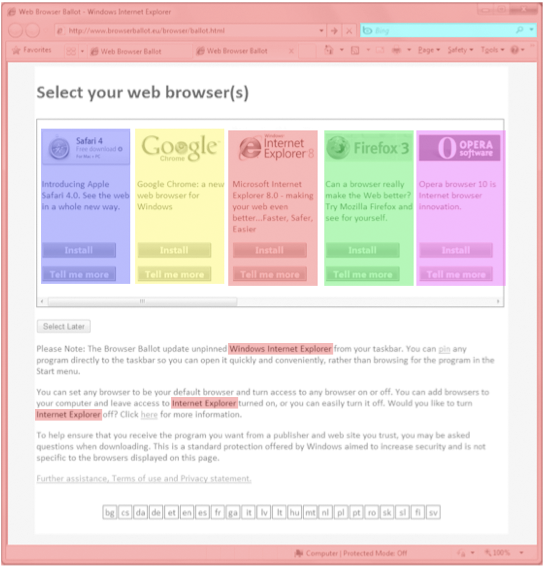

So, what will you see when this thing lands in trunk? Something like this:

Ugh, These Icons Aren’t Final, Are they?

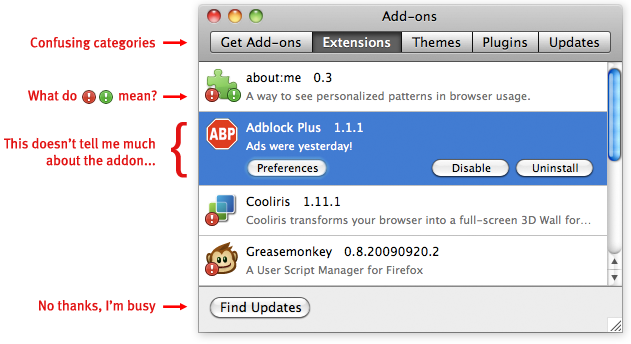

No, they’re not. Can you not read giant ridiculous gradient-heavy starbursts?! These are not the final graphics nor colors; they’re placeholders for now. In redesigning the add-ons manager, interaction design and visual design were kept deliberately separate. What you’ll see in trunk is a reflection of the new interactions in the add-ons manager – viewing in a tab, configuring and installing add-ons, etc. The final visual look will come later. This is partially because there’s still kinks to work out before the final graphics are created, and we’d like the community to try out the manager before it’s 100% done.

A Model for Firefox’s “Extra” Windows

There’s another reason the graphics aren’t final. If Firefox’s extra windows are going to move into the content area, they have to feel very different from the rest of the web. They need to feel fundamentally a part of the browser itself. They also need to feel like a part of Firefox and the operating system. Additionally, they need to feel like each other. One of the goals here is to make Firefox’s look and feel more cohesive. The browser is the one stable part of the browsing experience. The web is a dizzying array of different content, and the browser should provide a dependable framework for exploring it. Right now, Firefox’s style is inconsistent in many places, both in design and interaction.

It looks like different parts of Firefox were made by different people at different times because, well, they were. Compare that to a product with fewer people working on each feature’s interface and a much shorter turnaround cycle.

Incongruous design is often a result of software having an organic development cycle over a long period of time; different parts begin to look and feel very different to each other.

One way to mitigate against organic growth creating dissimilar design is to make and use style guides. Firefox follows them for code and terminology, but we don’t have much for interaction and interface design. So, before we can really bring all these extra windows to content, we need a clear picture of the interactions and style that we’re following. Starting this process has been contingent on the new Firefox theme becoming solidified. Stephen Horlander‘s done incredible work here, and we can feel confident moving forward with a plan for these other windows. This is a separate project that I’m starting up and will be blogging about in the future.

Design Influences

Even though the graphics and style are not yet final, I wanted to point out some of the projects that influenced the interaction of the add-ons manager redesign. Nothing is ground-breakingly new in the manager, and this is deliberate; I was trying to find the simplest interactions that would work for a wide variety of content and users.

One simple interaction being used is the two-panel design itself. “Zooming in” to information by moving right has become a standard of application design. All major operating systems have a similar interaction here: selecting an item on the left shows its contents and/or details on the right (the opposite is true for right-to-left language readers). This design is already being used in Firefox for the History sidebar, Bookmarks Sidebar, and Library.

The basic layout of the addon manager’s “digest” and “detailed” view are similar to the layout of addons on addons.mozilla.org (AMO). Luckily for us, AMO had a recent redesign and solved many of the problems of displaying add-on information. Giving summary information in a list helps find an add-on of interest, and more information is available on click. Using a similar style to AMO was also important because of how intrinsically the add-ons manager and AMO are related. Treating add-ons differently within Firefox would mean that add-ons users would have to learn two systems rather than one.

Other bits of the design are inspired by small interactions I’ve seen other applications get right. For instance, add-ons in the manager can be downloaded from within the manager. But, popping open the Downloads Manager to show a progress bar would clutter the interaction. I looked around for an elegant way to do in-content downloads, and found it in the video player Miro. Miro elegantly turns the download button for a video into a progress bar, meaning the user does not need to look away from the target they clicked on. They also incorporated pause and stop button beautifully into the bar itself. The new add-ons manager handles the progress bar very similarly.

Another element of Miro I thought was a good idea was the very subtle “Show More” button, which gives an expanded view of the selected item. This works well for add-ons as well as videos, and thus the redesign has a similar link.

The view of multiple add-ons was also inspired by task-management application Things, which also groups right-paneled items into expandable boxes.

Better close out before this gets too much longer. Tune in next time for: why themes are hard. Hopefully I’ll have a better title by then.

Recent Comments