At the end of this week, I’m moving on after six amazing years at Mozilla. On August 25, I’ll be joining Reddit – another global open source project – as their first user experience designer. I’m ecstatic to help shape and design the future of another incredible community.

In looking back at all that’s changed in technology and the web since I joined Mozilla, I find myself humbled at the trials we’ve met and overcome. When I joined in 2008, we were smaller and scrappier. Fellow designer Alex Faaborg and myself stood before whiteboards, explaining how tabs on top of the URL bar were more efficient. The bug backlogs of Firefox 3 kept us up at night, but when we launched in July 2008 we made the Guinness Book of World Records for most software downloads in 24 hours ((Mozilla sets new Guinness World Record with Firefox 3 downloads)). Chrome didn’t even exist yet!

Of the challenges in Mozilla’s future, many are nearly universal for open source communities and largely unsolved. Here are three I find myself often returning to:

1. How do we protect users’ data when users consistently choose utility over privacy?

You can package it any way you like, but if your privacy-centric product even slightly hinders user enjoyment of the web, it won’t see wide adoption.

When prompted, users overwhelming cite online privacy (referring to data being shared with companies and governments) as a concern. A recent poll ((Right To Be Forgotten: Do Users Even Care?)) showed 26% of people were “extremely concerned” about privacy when using a search engine, with nearly 90% expressing some level of concern. And yet, 92% of those use Google and only 3% use DuckDuckGo, an explicitly non-tracking search engine. In the developing world and younger markets, users are even less concerned. Mozilla’s research team is currently investigating attitudes towards privacy in Malaysia and the Philippines, and most people they’ve spoken with don’t even have a concept “online privacy” aside from not wanting their friends and relatives to see all they’ve posted to social media.

Those of us who care about online privacy are increasingly at a values impasse with our users. The solution is not to simply inform, coax, or frighten users into taking security measures.

Most importantly, a world without the practical technological possibility of privacy is much scarier than one where users can choose, either actively or passively, to share their information.

2. How can global communities accommodate incompatible values?

Championing inclusiveness and diversity is an easy decision for most organizations. But when push comes to shove, members of any large community will still disagree fundamentally on many important values. The need to bridge fundamental divides is an inevitability.

As an example, open source contributors disagree vehemently when it comes to DRM. Is it better to follow the content industry and implement extensions so content owners can control how users share content? Or, is DRM’s current instantiation so harmful to an open web that it’s worth limiting user’s access to content to avoid supporting it? Both these views and many others exist amongst Mozilla contributors, yet ultimately decisions about what ships in Firefox must be made. When this happens, the community cannot simply shrink by the number of people opposed to the decision.

To successfully cooperate, global communities have to form a sustainable plurality. The key is allowing members to operate in a context of known responsibilities to each other, yet also generalized freedom to hold, express, and act on their views. Freedom of expression should exist by default, but the community will collapse if members don’t understand that they also have responsibilities that are defined and understood.

Furthermore, the balance of power between the community at large and its leadership is best when it is understood and predictable. Major organizational decisions are often be made by a few executives or benevolent dictators for life. Where and how these decisions are made as well as what was decided needs to be widely available for a community to cohere. The community must also know the difference between the organizational values which guide decisions and the personal values of leaders which do not. Realistically, the two are never wholly separate.

The question over “public vs. private” values in leadership has been addressed frequently at Mozilla. Perhaps the lines that separate public and private views cannot be entirely explicit, but acknowledging and engaging openly about differences bring strength to a community. Again, this is best where the role and position of leaders in making decisions is clear.

3. How can design culture embrace open source?

Within design communities, open source is still met with disinterest at best and derision at worst. This is hurting both open source and design.

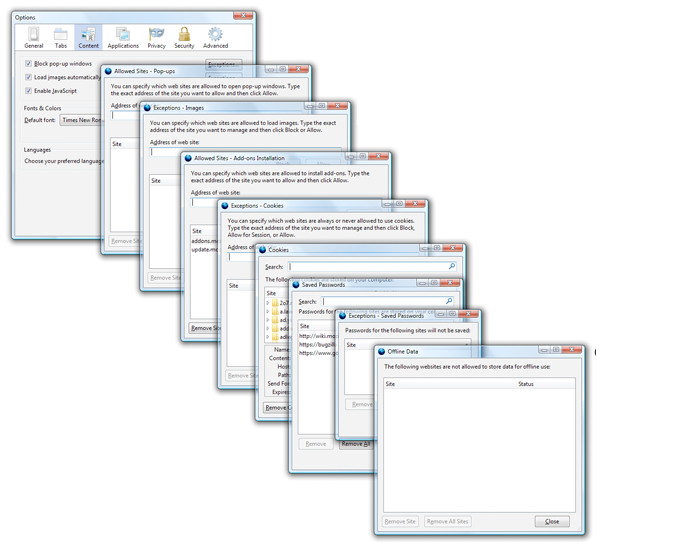

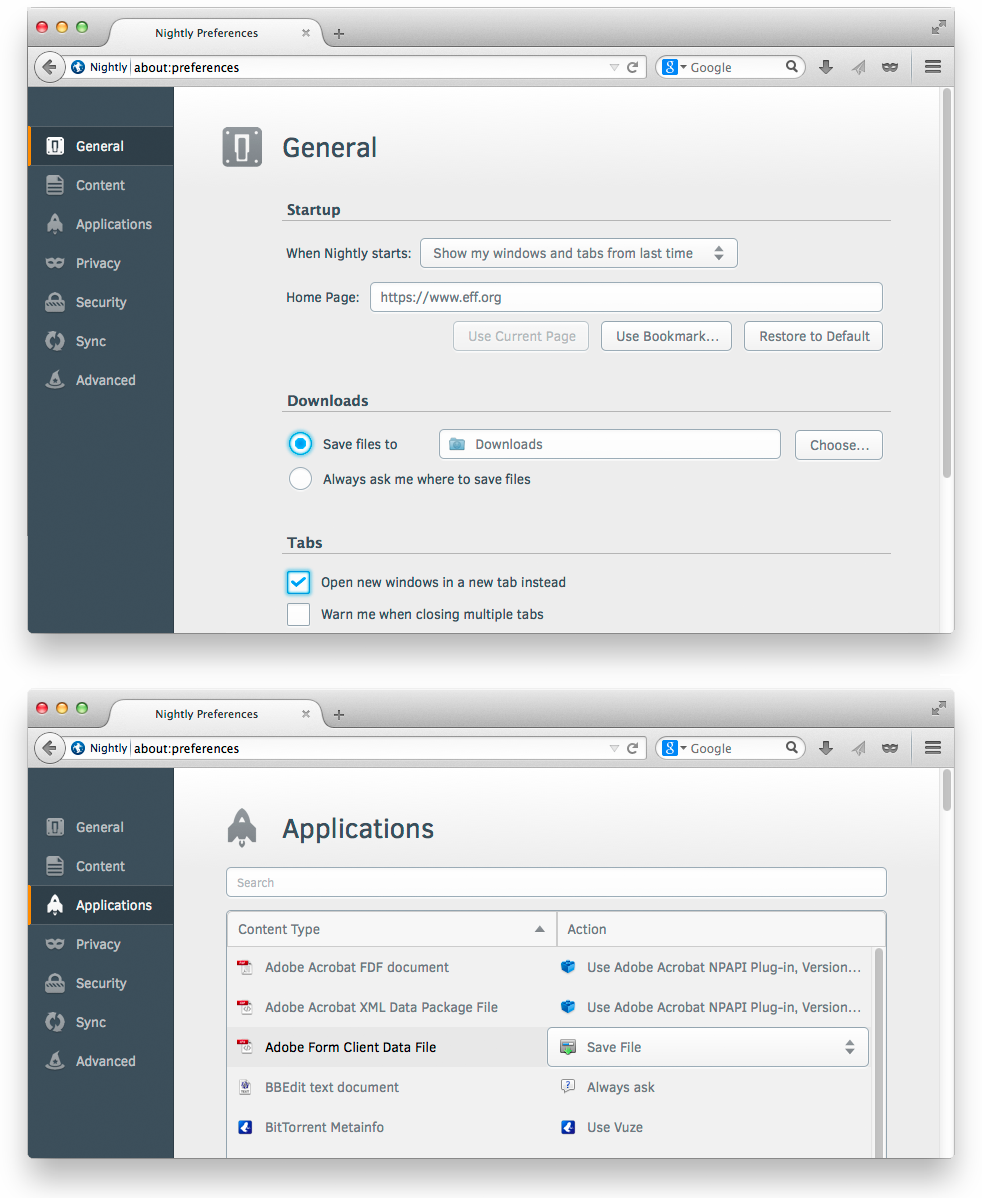

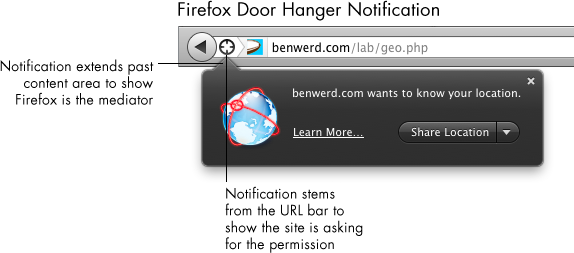

The main barrier towards design culture embracing open source is a chicken-and-egg: few open source projects appear to value usability and design. Scratch-your-own-itch hacker culture assumes the creators of technology are its users, which deemphasizes the need for usability and accessibility. Additionally, feedback in open-source is heard mainly from a few power-users, and the temptation to appease them can thwart designs that would appeal to a wider audience.

Another reason design culture hasn’t embraced open source stems from designers’ wariness over being taken advantage of. I remember Mark Mentzer, one of my Carnegie Mellon design professors, warning his students to “never work for free!” This attitude runs deep in design circles, and for good reason: we’ve become used to requests for work where the only payment will be “another piece in your portfolio.” Honoring those requests devalues design work as a whole.

But, open source is different from free labor. Just as developers do, designers love their work and often consider it a hobby as well as an occupation. The transformative potential of open source projects excites designers as much as developers. By insisting on excellent user experience, open source projects can show designers that they are communities that value design.

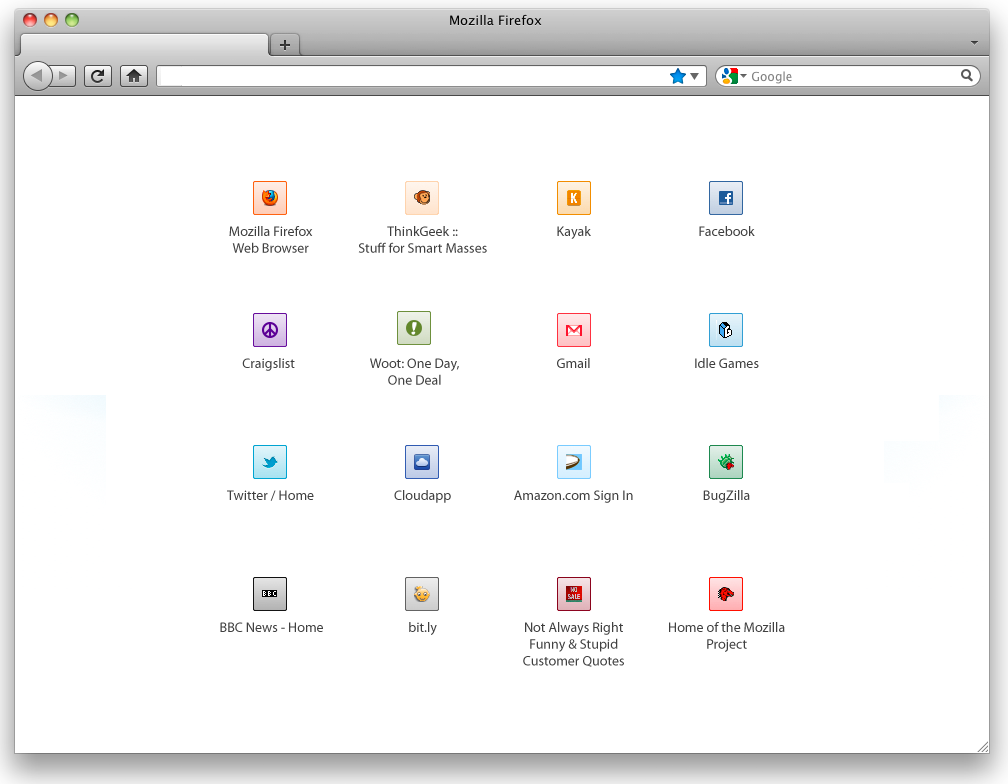

Another reason design culture hasn’t embraced open source is because code contributions fit more easily into open projects than design contributions. Any developer can jump into an open source project by taking and fixing a bug. Little context is needed beyond what’s provided in the ticket: current behavior, expected behavior, acceptance criteria. Patch written, reviewed, done, boom.

In design, more context and background is needed to “fix a problem,” which hinders potential community contributions. A design “bug” is harder to identify than most engineering bugs. Simply diagnosing them requires user research, collaboration, and context. Providing well-scoped design problems with dedicated mentors can help bring on contributors.

To Mozilla, thank you for six amazing years. You’re my allies, my friends, and the most incredible people I know.

Recent Comments