This past Friday, I went to Westfield Mall in San Francisco to conduct user tests on how people browse the web, and especially how (or if) they use tabs. This was part of a larger investigation some Mozillians are doing to learn about users’ tab behavior.

The mall is a fantastic place to find user test participants, because the range of technical expertise varies widely. Also, the people I encountered tended to be bored out of their minds, impatiently waiting for their partners to shop or friends to meet them. However, rather than completing all 20 tests I was hoping to, I ended up spending three hours testing a man I’ll call Joe.

I find Joe, a 60-year-old hospital cafeteria employee, in the food court looking suitably bored out of his mind. Joe agrees to do a user test, so I begin by asking my standard demographics questions about his experience with the internet. Joe tells me he’s never used a computer, and my eyes light up. It’s very rare in San Francisco to meet a person who’s not used a computer even once, but such people are amazingly useful. It’s a unique opportunity to see what someone who hasn’t been biased by any prior usage reacts. I ask Joe if I could interview him more extensively, and he agrees.

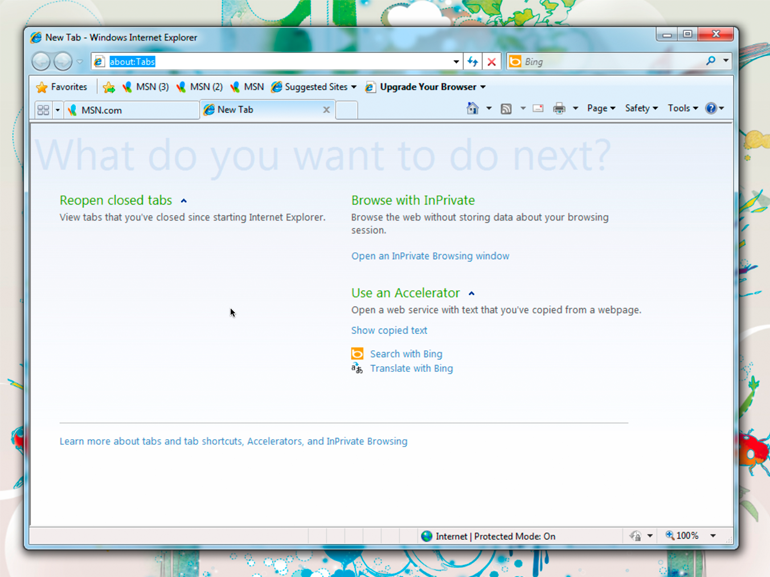

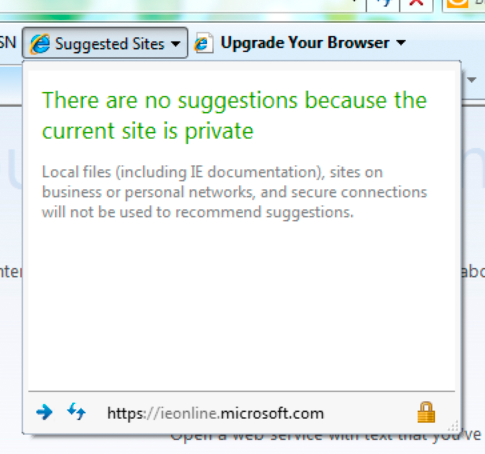

I decide to first expose Joe to the three major browsers. I begin by pulling up Internet Explorer.

Internet Explorer (as Joe encountered it)

Me: “Joe, let’s pretend you’ve sat down at this computer, and your goal is finding a local restaurant to eat at.”

Joe: “But I don’t know what to do.”

Me: “I know, but I want you to approach this computer like you approach a city you’re not familiar with. I want you to investigate and look around try and figure out how it works. And I want you to talk out loud about what you’re thinking and what you’re trying.”

(I show Joe how to use a mouse. He looks skeptical, but takes it in his hand and stares at the screen.)

Joe: “I don’t know what anything means.”

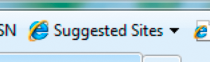

(Joe reads the text on IE and clicks on “Suggested Sites”)

Me: “Why did you click on that?”

Joe: “I don’t really know what to do, so I thought this would suggest something to me.”

(Joe reads a notification that there are no suggestions because the current site is private)

Joe: “I guess not.”

Joe looks around a bit more, but he’s getting visibly frustrated with IE, so I move on to Firefox.

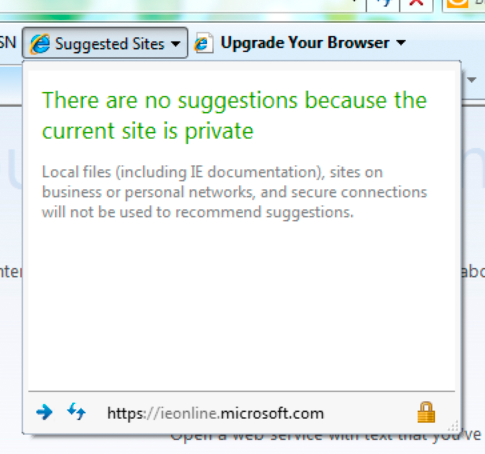

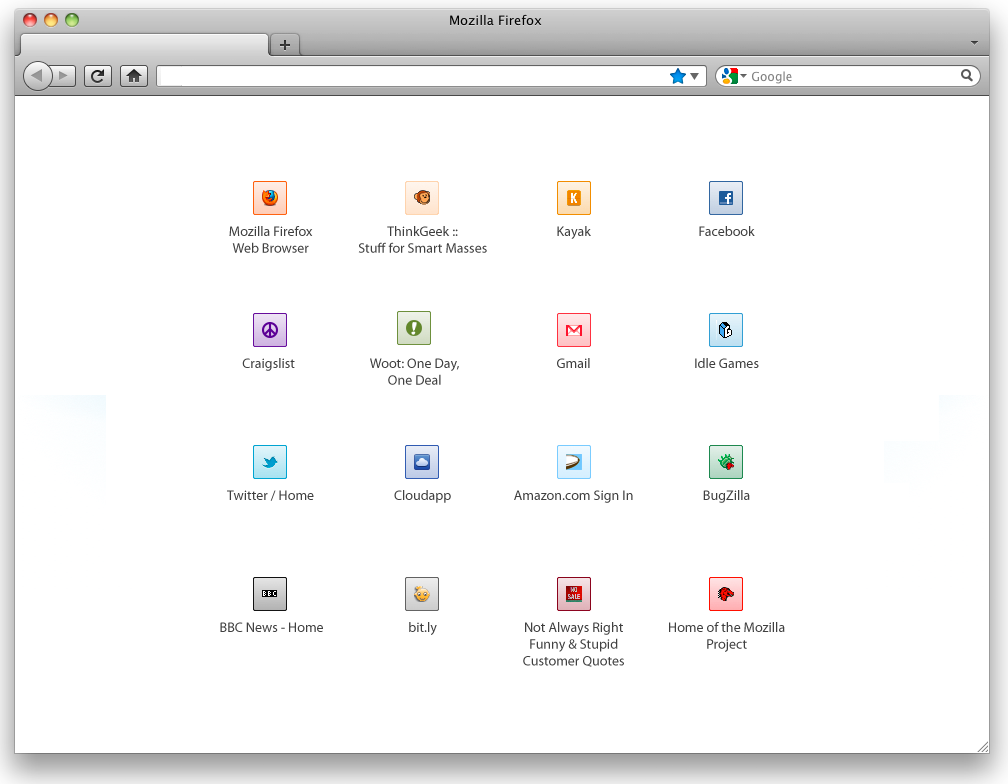

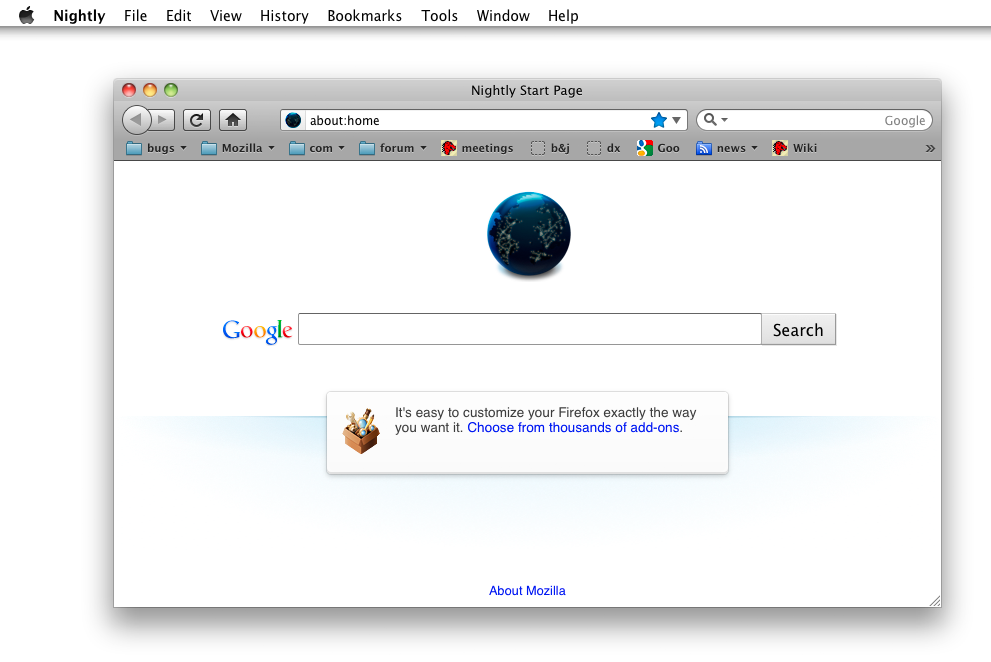

Firefox (as Joe encountered it)

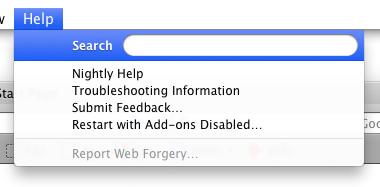

I give him the same task: find a local restaurant. He stares at the screen for awhile with his hand off the mouse, looking confused. I ask what he’s looking for. “I don’t know, anything that looks like it will help!” he says. Finally, he reads the Apple context menu at the top of the screen, and his gaze falls on the word Help.

“Help, that’s what I need!” says Joe. He clicks on Help, but looks disappointed at what he sees in the menu.

“None of these can help me,” he says.

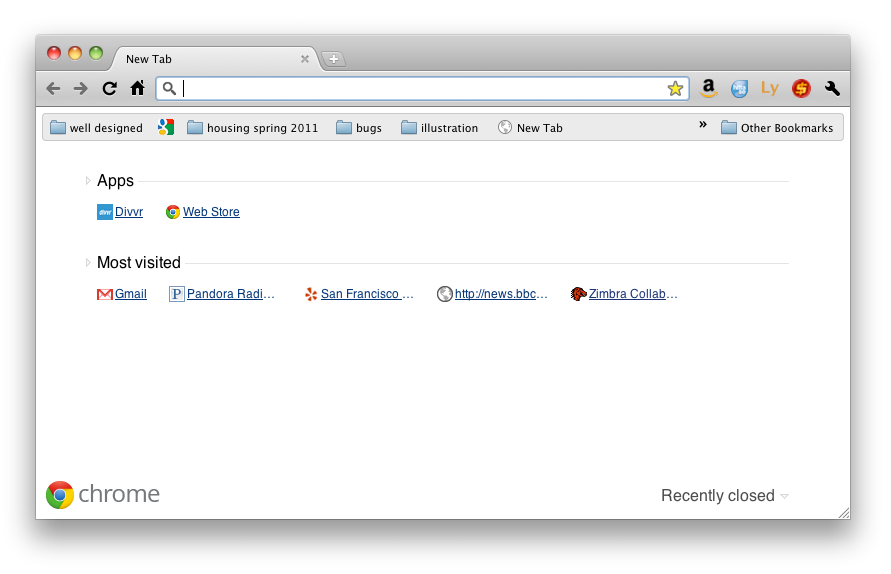

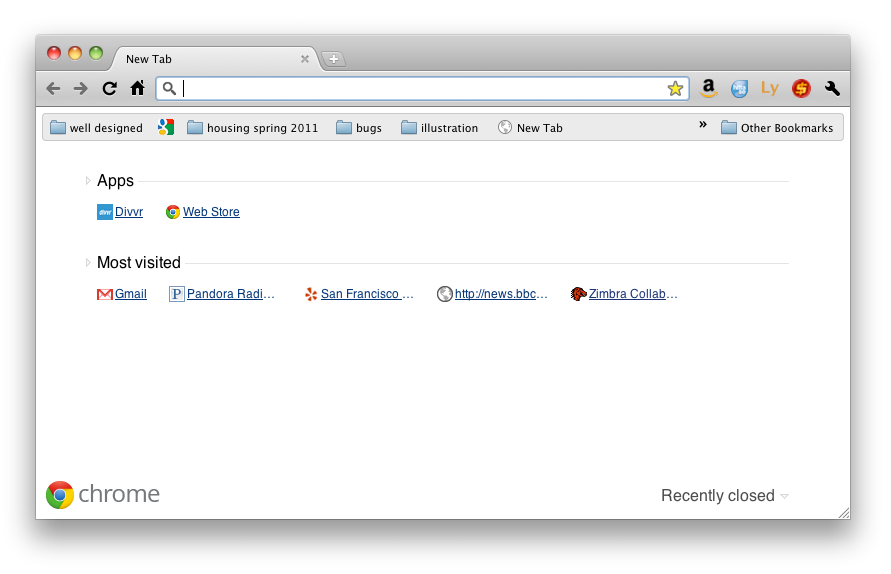

Joe is getting frustrated again, so I move on to Chrome and give him the same task.

Chrome (as Joe encountered it)

He proceeds to read all of the words on Chrome’s new tab page, looking for any that may offer guidance. Luckily for Joe, he spies a link to Yelp which is marked San Francisco in Chrome’s new tab page. He clicks it, and, seeing restaurants, declares he’s won.

I want to put Joe through other experiments at this point, but the tests are clearly taxing him. He looks very agitated, and has frequently in the tests declared that he “just doesn’t know,” “should have learned this by now,” and “has no excuse for not taking a class on computers.” No amount of assurance that I was testing software, not him, was calming him down. So, I decide to cut Joe a break. “Alright Joe, you’ve helped me, maybe I can help you.”

Because Joe has mentioned a few times he wants email, I get him a gmail.com email address and show him how to access it at a public computer. We practice logging into Gmail several times, and I end up writing a very explicit list of steps for Joe which includes items like “move mouse cursor to white box.” One of the hardest things to relate to Joe is the idea that you must first click in a text field in order to type.

When I am convinced that Joe understands how to check his email, I want to show him how he can use his new email address. So, I ask him why he had asked for an email address in the first place. I imagine he’ll say he wants to communicate with friends and relatives.

Joe: “I want discounts at Boudin Bakery.”

Me: “Sorry, what?”

Joe: “I want Boudin discounts, but they keep telling me I need email.”

(Joe takes his Boudin Bakery customer appreciation card out of his wallet and shows it to me)

I’m a little confused, but go ahead and register Joe’s Boudin Bakery card with his new email address. I show him the web summary of all the bread he’s bought lately. “Woah!” says Joe.

So, what did I learn from Joe?

- There is little modern applications do to guide people who have never used a computer. Even when focusing on new users, designers tend to take for granted that users understand basic concepts such as cursors, text boxes, and buttons. And, perhaps, rightfully so – if all software could accommodate people like Joe, it would be little but instructions on how to do each new task. But, Joe was looking for a single point of help in an unfamiliar environment, and he never truly got it – not even in a Help menu

- No matter their skill level, users will try to make sense of a new situation by leveraging what they know about previous situations. Joe knew nothing about computers, so he focused on the only item he recognized: text. Icons, buttons, and interface elements Joe ignored completely

- We shouldn’t assume that new users will inquisitively try and discover how new software works by clicking buttons and trying things out. Joe found using software for the first time to be frightening and only continued at my reassurance and (sometimes) insistence. If he was on his own in an internet cafe, I think he would have given up and left after a minute or so. Giving visual feedback and help if someone is lost may help people like Joe feel they’re getting somewhere

- Don’t make too many assumptions about how users will benefit from your technology – they may surprise you!

Recent Comments