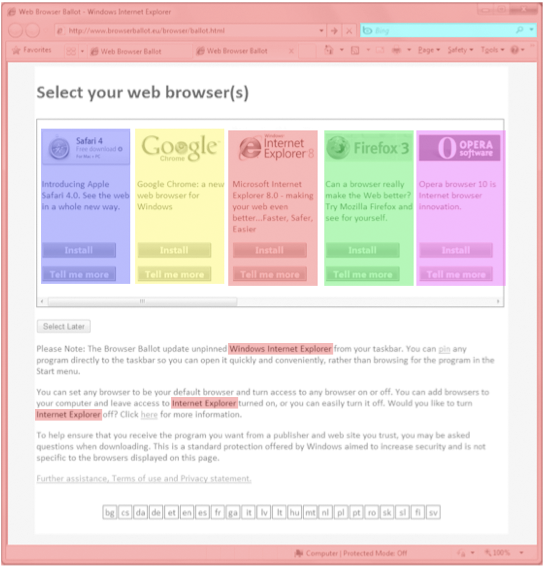

You’re probably familiar with the whole European Commission/Microsoft browser case. Long story, but basically the EC accused Microsoft of harming consumer choice by bundling Internet Explorer with Windows, Microsoft offered to present users with a browser ballot, I wrote about how a ballot wasn’t a great solution but should be designed well, yadda yadda. Last month, Microsoft agreed to show the browser ballot choices in random order, rather than fixed. Definitely an improvement!

I still wondered what effect, if any, item order and other variables would have on what browser people would choose. Would certain design changes on the ballot have a big impact on users? And how could Firefox optimize its space on the ballot to be most effective?

Mechanical Turk: The Odds are Good, the Goods are Odd

My colleague Alex Faaborg suggested that I try using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to get some answers to these questions. Mechanical Turk lets users create tasks that they need humans (called workers) rather than computers to perform. Workers select tasks that look interesting to them and are paid a small amount for each task completed. I was pretty skeptical about using any pay-for-answers service at first. My fear was that workers would be a strange grabbag of too-technically-competent-to-be-representative people who would go through tasks at lightening speed, barely reading them, to get the most profit out of their time. But I was curious about how well the system worked and tried it out with a series of tests. Some of these presented workers with ballots, and others asked workers to compare different aspects of Mozilla’s branding within the ballot.

I was actually amazed at how well the Turk performed, and especially at the ludicrous speed at which workers responded. Within four hours I had the time of about four hundred workers, each spending an average of three minutes on a short seven-question survey that I thought would take 20 seconds. To my surprise, the vast majority of free-form answers were filled in with thoughtful detail. Numbers of people this large, for that kind of time, for so little money (each worker was paid ten cents USD) was pretty sweet. It’s frightening how the hive mind’s torrential force is so easily bribed.

The bad news is that as suspected, the Turk workers are a strange sample. They skewed heavily towards living in North America and being more technical than an average users. Of my workers, 49.35% were already using Firefox (compared with 31.34% worldwide), and only 18.44% were using Internet Explorer (compared with 55.53% worldwide). However, those free-form answers were pretty effective at separating geeks from n00bs, and it’s n00bs I was interested in.

So what are the results already?

Ok, ok. For the majority of tests, I presented users with a browser ballot with some small variables changed – maybe a different Firefox logo, a different description, etc – and had users select a browser as though they were being given the ballot when starting Windows. Unsurprisingly, no change to Firefox’s logo nor description on the ballot made a statistically significant difference to what browser workers selected. But people were in the mood for change: 29.09% of people wanted to switch browsers when presented with the ballot. Internet Explorer users were most likely to want a new browser – 38.03% of them changed teams. Opera users were most loyal, with 92% staying on Opera. 70.53% of Firefox’s users wanted to stay with Firefox.

Of those Firefox users who wanted to switch, 51.79% wanted to try Chrome. Of Chrome users who wanted to switch, 50% wanted to try Firefox. It’s not too surprising that there’s crossover – both Chrome and Firefox attracted the more tech-saavy users who followed browser innovation to some degree. What’s interesting is that the main reasons people gave for switching to Firefox and Chrome from any browser were related to brand recognition. Nearly everyone who wanted to switch to Firefox said they’d “heard good things” about it, or that an acquaintance had recommended it. Most switching to Chrome mentioned using and liking Google’s search engine and being curious to see what else Google could do. In Firefox’s case, recognition was based on recommendation. In Chrome’s case, recognition was all about the familiar logo associated with successful searching.

Of Internet Explorer users – the only ones who will actually see the ballot – 22.53% wanted to switch to Chrome, 8.45% to Firefox, and 7.04% to Opera. I should note that I believe the high Chrome percentage is partially because this sample of people make part of their income through the browser and are thus more familiar with the Google brand than your average European Joe. However, it does show a huge momentum towards Chrome, fueled by that all-important brand recognition.

So what else made people switch browsers? Workers had many associations with browsers – even those they didn’t use. They described both Chrome and Firefox as fast, easy to use, and innovative. Most users sticking with Internet Explorer described it as being familiar, or that they were content with their current browsing experience. However, there was one association that workers only made with Firefox: security. Nearly every comment relating to security and privacy was in support of Firefox, and most of those who would consider switching to Firefox mentioned this as a personal priority.

Below is a graph of how the workers responded to the ballot. Unsurprisingly, most people voted for the browser they were using, shown by a strong top-left to bottom-right diagonal.

If these results were extrapolated, it would dramatically change the browserscape of Europe. Internet Explorer would lose 38.03% of its European market share, Chrome would gain 10.11% the European share, and Firefox would gain 3.79%. Again, these results are highly skewed towards Chrome because of the Mechanical Turk sample, but I do think that Chrome will probably emerge as a big winner of the ballot screen. The Google brand is well known and well established, and I believe it will cause users to recognize Google as a brand they already use thus try Chrome.

Recent Comments